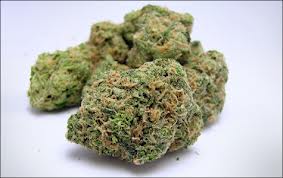

By Daniel Nasaw BBC News Magazine, Washington This month, two US states voted to legalize, regulate and tax marijuana. From advertising and marketing to drugged-driving enforcement. The 6 November votes in Colorado and Washington left a lot of marijuana users happy and a lot of police officers nervous. And they set the two states up for a confrontation with the federal government, as marijuana is still illegal under federal law. Marijuana is the most widely used illicit drug in the US. Legalization advocates say the recent votes mark the beginning of the end of the drug's prohibition. "It's a tipping point for sure," says Sanho Tree, director of the drug policy project at the Institute for Policy Studies. "If these two states go ahead and legalise recreational use and the sky hasn't fallen, that opens up more political space." But authorities are wary. "The Colorado chiefs of police are incredibly concerned with regard to public safety as a whole," says Chief John Jackson of the Greenwood Village police department, and legislative chair of the Colorado Association of Chief of Police. Nearly 80 years after the US ended the prohibition of alcohol, we aim to answer just a few of the questions raised by the movement. How will retailers and growers market and advertise marijuana? The laws forbid under-21s from possessing marijuana, and Washington bars marijuana adverts from within 1,000 ft (305m) of schools, playgrounds, parks and other places children gather. To the uninitiated, different kinds of marijuana look and smell pretty much the same and when smoked, have more or less the same effect. Once it becomes a legal consumer product, how can Washington and Colorado companies in the marijuana business build brand identity and expand their market? "Whether it's socks or weed the first thing you have to do is look at who's your target," says Rahul Panchal, an advertising creative director in New York. Panchal says the core market is well established: "Mid-twenties stoner guys". Those people are already comfortable smoking marijuana and are happy to buy it with minimal packaging or advertising effort. Successful marijuana entrepreneurs will try to expand that market, for example by tapping into existing subcultures or identity groups, for example outdoors enthusiasts, health-conscious suburbanites or stressed out professionals. An enterprising grower or retailer could develop a premium marijuana brand using high-design packaging to project an aura of exclusivity. "Gold leaf, black background," imagines Peter Corbett, chief executive officer of iStrategyLabs, a Washington digital marketing and advertising agency. "The packaging has a matte finish, so it's tactile and feels expensive. It would never come in a plastic bag - it comes in a linen sack." Entrepreneurs in search of big profits should look at the dairy industry, says Panchal. "The lowest margin is to just sell milk," he says, while the real money is in processed products like cheese and yogurt. "I would sell pot products: cookies, brownies and such. That's where the money's going to be." Police do not need blood tests to catch stoned drivers, says a Colorado police chief. Can your boss still make you take a drug test?

An evening joint around a camp fire in Colorado, though perfectly legal in that state, could still threaten your job, because the new Colorado law specifically lets employers forbid marijuana use among workers. "This isn't forcing any kind of change," says Mason Tvert, co-director of the Campaign to Regulate Marijuana like Alcohol, which advocated for the Colorado initiative. Washington's law does not specify either way. But workplace drug testing is already on the decline, says Lewis Maltby of the National Workrights Institute. He and Tvert predict employers in Colorado and Washington will now be even less inclined to test employees or prospective hires. Most drug testing, including pre-employment screening, is based on the perception that off-duty drug use among workers is bad for business, not on hard evidence, Maltby says. Most people who fail workplace drug tests are what he calls "Saturday night pot smokers", not people who smoke before work and are simply unable to get the job done. "Since it was fear that drove the testing in the first place, when marijuana becomes less scary a few less employers will test," he says. How can police officers prevent drugged driving? Both state referenda forbid driving while under the influence of marijuana. But a driver can have marijuana in his blood and not necessarily be too stoned to drive, since marijuana remains detectable in the body days and even weeks after use. The Washington law sets a threshold of five nanogrammes of THC, the active ingredient in marijuana, per litre of blood, and Colorado's legislature is expected to enact a similar threshold. Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich of Spokane County, Washington says officers who suspect a driver has smoked too much will have to summon a paramedic to draw blood for a test. "How much of an added expense is that going to be to our agencies?" he asks. Police have plenty of other ways to detect drug driving, says Chief Jackson: "I don't need a toxicology test on the side of the roadway." If officers see motorists driving erratically, they can stop and interview them and ask them to perform field sobriety tests. The encounter will likely be filmed from a dashboard camera. If the officer believes a driver is impaired, the officer will make an arrest and later testify in court, Chief Jackson says. "You don't need breathalyser tests to convict drunk driving," he says. "People refuse to blow all the time but we still convict them in the state of Colorado."

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Your new style scene

Archives

December 2015

|

©MySceneTV - MSTv Productions, LLC | [email protected] | P 504.491.0254

RSS Feed

RSS Feed